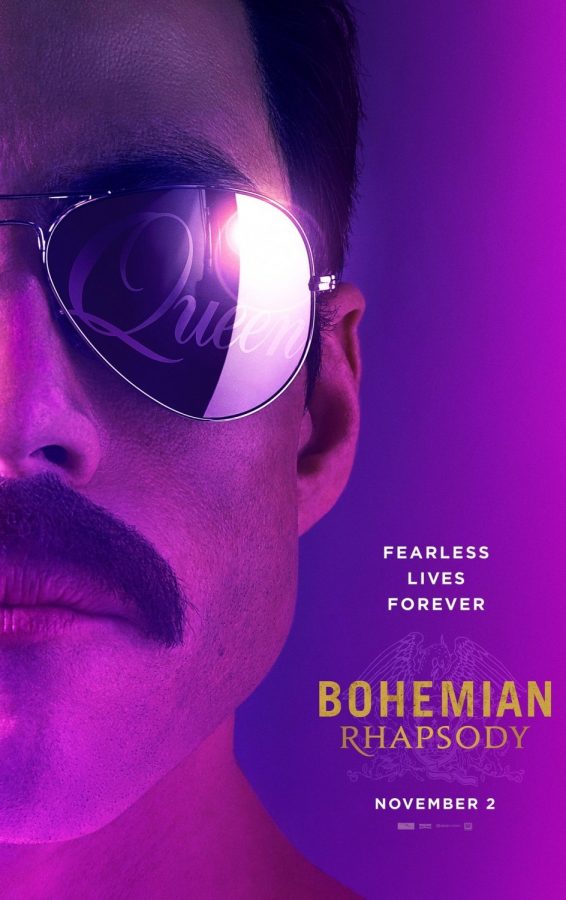

In December of last year, I attended a midnight screening of what I and many others call the world’s most beloved bad movie: The Room, brought to life by the ironically illustrious Tommy Wiseau.

Written, directed, and produced by Wiseau — a mysterious figure described by WIRED as a “shambolic” cult celebrity — The Room was an attempted true tragedy that would have put Shakespeare to shame. Its plot revolves around the infidelity of protagonist Johnny’s fiancée Lisa, who cheats on him with his best friend Mark, played by Greg Sestero. Accompanying them are Lisa’s brash mother, the relaxed psychologist Peter, the rage-induced dealer Chris-R, and others who all seem to be the result of some concussed creative impulse. The Room’s plot attempts to explore a motley crew of unconcluded storylines, from breast cancer to a botched drug deal, and almost exclusively centers around one set: Johnny’s apartment and the titular room.

The movie itself is one of the worst I’ve ever seen, full of filming inconsistencies, continuity errors, obvious lack of proper set decor, painfully choreographed “love” scenes, and shaky dialogue. Amidst the thousands of available films and hundreds released annually, then, how does such a crapshoot captivate so many? When Wiseau set out to create a good movie but did the exact opposite — diluting his reputation to that of the brains behind the best bad movie — did he simply become one of the many other pigeonholed actors in Hollywood?

The film would have faded into irrelevance in wake of its 2003 critical and financial failure after two weeks at the Laemmle Fairfax and Fallbrook theater, but it still wasn’t allowed to die. As time passed, it was given new life by blooming, devoted groups of followers, becoming a cult classic and gaining popularity underground among movie fanatics.

As the film screenings sold out nationwide, interactive activities began to grow in popularity: spoon tossing, thanks to the constant use of framed spoons; football throwing, given their symbolic presence in the movie; and impersonating the film’s characters, yelling along with the infamous lines.

The film itself has even become a facet of pop culture, not only as a source of memes, but also as famous actors like Jonah Hill, Paul Rudd, and Kristen Bell have identified as serious fans of the film. A late 2008 Entertainment Weekly spread entitled “The Crazy Cult of ‘The Room”’ analyzed the film’s still-developing cult and how it showed “that there is room—in Hollywood for Tommy Wiseau.” Along with other media sources, it propelled Wiseau’s film out from underground culture into the limelight of the public eye.

Most of the cast — at least the ones who haven’t fallen into obscurity — have similarly become largely reliant on The Room’s infamy for success: The Room made their careers and then blacklisted them from any serious credibility. Now with an exposé best-seller, world-wide praise, constantly sold-out showings, and a critically-acclaimed “based-on-a-true-story” film, perhaps its classification as a cult film should be revised.

But that’s the point: The Room is a good film only because it is a bad film. Its label as a “cult classic” only confirms the underlying disrespect that comes with the love for The Room.

The film’s impact on Wiseau’s career, however, is far sourer than its popular status: to be loved by the members of a society he so desperately wanted to be included in is ultimately a cruel joke on Wiseau’s behalf. He had always wanted to act, but his general “look,” emotional instability, blatant obliviousness, and absolutely muddled accent left him with no prospects in the acting scene. Wiseau thus attempted to give himself a chance when no one else would, setting out to make his way into the inner workings of Hollywood with what he is known to consider a masterpiece, but it only was the trainwreck nature of the film and this cult following which brought him there, rather than through the acclaim he had so desperately coveted.

Categories:

Film Fanatics: Failed masterpiece becomes 'cult classic' with The Room

March 12, 2018

Donate to The Newtonite

More to Discover