Originally published in print Friday, Jan. 20, 2017.

Just two weeks after Massachusetts voters struck down a measure to raise the cap on charter schools, president-elect Donald Trump nominated as his Secretary of Education one of the strongest pro-charter advocates in the nation. Now, in the wake of an election that has sent shockwaves throughout the country, many Americans—including here in Newton—fear that the face of K-12 education could change drastically over the next four years.

“Donald Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Education and people that support charters and vouchers don’t think education is a public good,” said Newton Teachers Association president Michael Zilles. “They think education should be treated like a car: you get what you pay for.”

Education secretary nominee Betsy DeVos has proposed awarding government funds to private and parochial schools through a voucher system in which children would be permitted to attend at a reduced cost. In her home state of Michigan, she has also advocated the replacement of traditional public schools with charter schools—tuition-free, public schools that receive a special degree of autonomy.

While the notion of vouchers bears little resemblance to any prior national policy, the charter question has long been a point of controversy. Proponents argue that charter schools—with their innovative teaching and management methods—offer top-tier educational opportunities to students who would otherwise languish in troubled district schools. Those who oppose charters, such as Zilles, say that these schools siphon money from traditional public schools, create hostile environments for English as a Second Language (ESL) students and special needs students, and lead to de facto segregation within districts.

In a state where popular views on education are now at odds with those of national policymakers, the question of how charter schools fit into the equation remains pressing. The issue does not fall neatly along party lines, and Newton residents have expressed mixed feelings.

Consequences for Newton

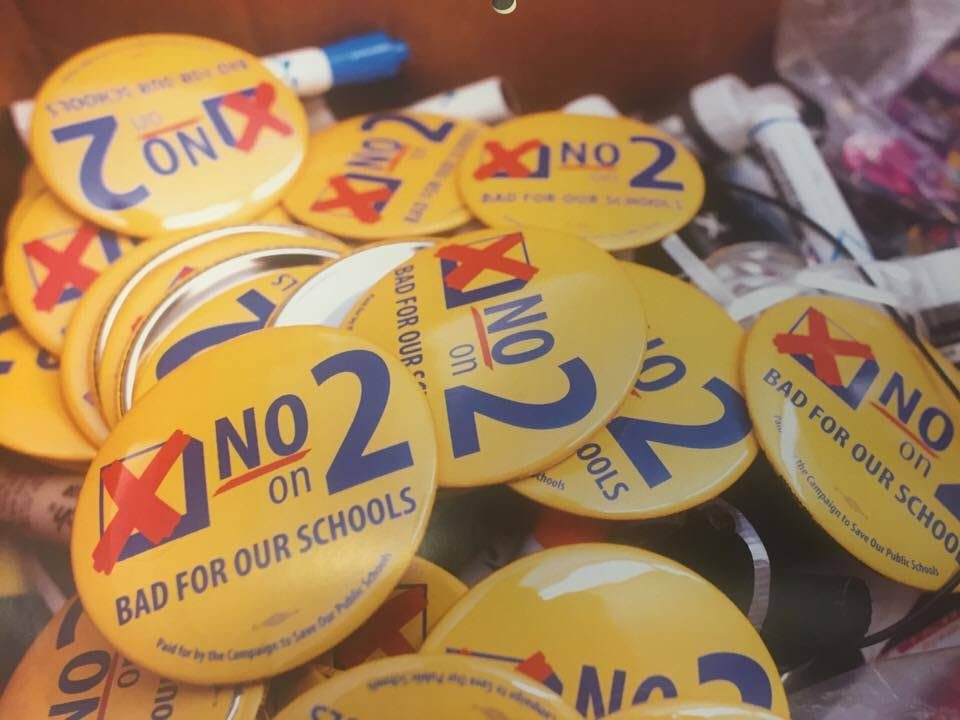

In the weeks and months leading up to election day, Proposition 2 (Prop 2) became an important topic of conversation among students and teachers. Prop 2 would have “allow[ed] the State Board of Education to approve up to 12 new or expanded public charter schools a year” had the measure passed, according to CBS Boston.

Senior Gregory Brumberg, a student representative to the School Committee, recalled that his history teacher had worn a shirt or button expressing opposition to Prop 2 and that he and his teacher had discussed the matter together.

“I asked him why, and I said, ‘I know that’s the view I’m supposed to have—can you explain to me why I’m supposed to have that?’” Brumberg recounted. “And he explained to me how it [the emergence of charter schools] was taking away funding.”

Following his teacher’s advice, Brumberg ultimately voted “no” on Prop 2. Yet Brumberg said he doubts that a “yes” verdict would have had any direct impact on Newton students.

“A lot of my friends had the same thought that I did—that charter schools take away funds from public schools. But I think that’s a little bit misguided because the bill gives priority to charter schools that would open up in under-achieving districts,” he said. “So I just feel like students weren’t quite informed about that because it wouldn’t necessarily be taking away from Newton Public Schools.”

Brumberg is correct that Newton has not yet become home to any charter schools. However, Zilles said that if Prop 2 had passed, the measure would have “made the emergence of a charter school in our district very likely. They would have tried to open a ‘boutique’ charter, like a language immersion school or a STEM or STEAM school,” he said.

Moreover, individual school districts lack jurisdiction on the charter question, since decisions take place at the state level. “It wouldn’t have mattered if the Newton School Committee had said, ‘we can’t afford that,” Zilles explained. “We would have had to pay for it.”

The funding question

The root of Zilles’ concern about affordability lies with the fact that charters receive funding on a per-pupil basis: if a student in a given district chooses to attend a charter school rather than a traditional public school, the charter school receives a sum of money equivalent to the average cost of educating a student in a public school. In turn, the public school loses that same sum of money.

Zilles noted that this process can result in a significant reduction of funding without a real reduction in cost, since “you still have to run your buildings and operations.”

“The other thing that happens is, the students you take out are mostly not high-needs. That means the per-pupil cost of education in public schools goes up,” Zilles added.

In an op-ed in Commonwealth Magazine, Thomas Kane, a Newton resident and a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, attempts to soothe concerns about funding: “The state law recognizes that district schools have commitments regarding staffing and facilities which are difficult to adjust quickly when demand declines,” Kane writes. “Therefore, the state law seeks to soften the transition, by paying both the district and the charter school for the first year after a student has left and by continuing to reimburse the district for one quarter of the students’ cost for the subsequent five years.”

Charter performance in Massachusetts

While pro-charter advocates such as Kane have evidently worked to refute claims that charters siphon funds from traditional public schools, the main argument these proponents put forth rests on the quality of the charter schools themselves. Those in Kane’s camp argue that Massachusetts charter schools educate students far more effectively than do traditional public schools.

In Boston, at least, there is evidence that charter schools help narrow the achievement gap with regard to income and race, according to a New York Times op-ed. In a piece titled, “Schools that Work,” Times writer David Leonhardt explains, “The gains are large enough that some of Boston’s charters, despite enrolling mostly lower-income students, have test scores that resemble those of upper-middle-class public schools.”

According to Boston Magazine, moreover, “The average SAT composite score in Boston’s charter high schools in 2015 was 100 points higher (about 10 percentile points) than the district schools.”

Here at North, some students are familiar with this argument and acknowledge its merit. Senior Izzy Tils has received an inside view into the experiences of students who attend charter schools through her work with Boston Cares, an organization that coordinates community service projects among teens from the Boston area. Two of Tils’ peer collaborators attend charter high schools, and in preparing to vote this past fall, she asked these students about their experiences.

“They were saying that although a lot of kids don’t get this opportunity, for the kids who do, it really changes their lives for the better,” Tils said. “They were saying, ‘we want more kids to have this opportunity.’”

While Tils noted that her conversations with these students certainly “put things in perspective,” she still felt the need to do significant research before casting her vote. She ultimately voted “no” after learning more about the potential risks associated with charter schools.

“I read this article that talked about how we think charter schools are an equal opportunity for everyone because you don’t have to pay,” said Tils. “Even though you apply, it’s free, which creates a very diverse group of people.”

Upon reading further, she realized that “the admissions process isn’t as equal as we thought, just because in order to actually write an application … your parents have to be educated enough to do that.”

Indeed, while charter schools admit students indiscriminately—employing a lottery system rather than selecting based on prior academic performance—the very act of applying suggests a degree of parental involvement that could help explain students’ academic success. Zilles, similarly, believes that charter schools begin with a different pool of students than traditional public schools and that it is dishonest to attribute their success to the charter school environment.

Researchers have tried to take this concern into account when evaluating the success of charter schools. Some have compared the achievement of students who attend charter schools to that of students who apply but lose the lottery.

“At the time of the admission lottery, those applicants who are offered a slot at a charter school and those who are denied are indistinguishable; they have the same prior achievement, parental engagement, and motivation,” writes Kane. “Yet, when I and a group of researchers from Harvard, MIT, Duke, and the University of Michigan subsequently tracked down the admission lottery winners, and compared their outcomes to the lottery losers, we found large differences in achievement.”

While he notes that “Boston charter schools truly are a cut above charter schools nationally,” Kane claims that the data favors Boston charter schools over traditional public schools. According to Kane, in the course of just one school year, “Oversubscribed charter schools in the Boston area are closing roughly one-third of the black-white achievement gap in math and about one-fifth of the achievement gap in English.”

Zilles nevertheless believes that Kane’s data is distorted and that the research that has been conducted does not constitute a “pure experiment.”

“When they look at the pool of kids accepted in charters and those on waitlists, only high-performing charters have waitlists,” said Zilles. “It’s as if you took kids from Boston Latin School and compared them to the rest of the Boston Public Schools—it’s a false comparison.”

He added, “It also doesn’t look at the fact that some of the kids don’t end up remaining in charters.”

Potential barriers among students

Another major area of controversy relates to charter schools’ abilities to accommodate students who are non-native English-speakers and students who have special needs.

In an op-ed in the Newton Tab, Zilles cites the Fall River Public Schools as an example of a district in which charter schools have created barriers between students with differing degrees of proficiency in English.

“Charter schools in Fall River do not serve English language learners….They create a segregated, two-tiered system where children with higher needs are concentrated in the public schools.”

In an interview with The Newtonite, Zilles added that charter schools are “not hospitable environments for students who have special needs.”

Kane acknowledges that “students with special needs and English language learners were underrepresented in charter schools for many years” but explains that the state has been working to fix this issue through policy changes.

“[I]n 2010, the legislation required charter schools to submit plans to actively recruit students with special needs and English language learners,” Kane writes. “Moreover, the legislation required the state board to consider schools’ success in recruiting and retaining students with disabilities and English language learners when renewing a charter school’s right to stay open.”

Zilles remains skeptical. “Charter advocates have talked about how they’re increasing the numbers of services, but the numbers are false,” he said. “Even though they may have been increased to some extent, those are the children with the most moderate needs.”

Trump's pro-charter stance clashes with state's 'No' vote on Prop 2

February 7, 2017

0

Donate to The Newtonite

More to Discover