by Peter Diamond

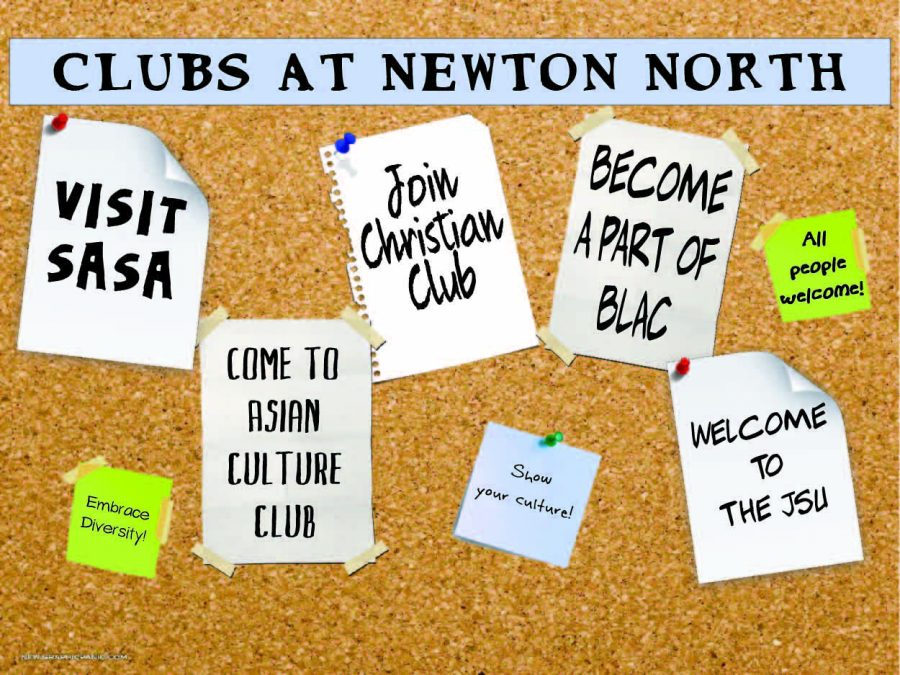

There is an undeniable racial achievement gap in this school. Honors and AP classes almost all have a white majority, and despite its core value of diversity and programs dedicated to closing this gap, this school, like any other, is impacted by prejudices held against students of color.

Newton exists in the backdrop of Boston’s de facto segregation. The Metropolitan Council of Educational Opportunity (METCO), founded in 1966, sends students of color from the inner city to the Newton Public Schools, but the program has often been met with violent pushback. As recently as the 1990s, public displays of animosity have occurred on this school’s Main Street against METCO students.

Much of the prejudice against students of color comes from an image of white formality, or the idea that treats types of dress and speech from white culture as the norm. Many of this school’s most successful students reflect white formality, which makes us susceptible to the idea that blacks who reject that norm (students who speak in standard black vernacular or who dress in a traditionally black urban fashion) are somehow threatening, or “thugs.”

As recently as the 1990s, public displays of animosity have occurred on this school’s Main Street against METCO students.

The standards and stigmas of white formality and the “thug image” may be at the heart of racial violence nationwide, such as that in Ferguson.

Almost 2,000 miles away, racial violence has reached a climax unlike any Newton has seen. On Saturday, Aug. 9 at 12:01 p.m., police officer Darren Wilson of Ferguson, Missouri shot 18-year-old Michael Brown to death. Like the shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2011, the Ferguson incident looks like another case of an epidemic of excessive force used by people in positions of authority against young black men.

Newton students must acknowledge that the idea of a “thug image” is rooted in racism.

In discussing Ferguson, Newton students should focus on the issue of racial violence in general, not the images that certain media have used in portraying Brown. What Brown may or may not have done before the shooting does not reflect the underlying problem (some testimonies argue that Brown had robbed a convenience store earlier that day, or that, although unarmed, he assaulted Wilson). Those images should not distract from the fact that six gunshots against an unarmed teenager from 20 feet away is excessive force.

Sources including the Wall Street Journal, Fox News, and National Review Online have accentuated a “threatening” image (threatening by a standard of white formality) in their portrayal of the victim, as well as his alleged petty theft, as if to suggest that Brown somehow deserved to die.

In discussing Ferguson, Newton students should focus on the issue of racial violence in general, not the images that certain media have used in portraying Brown. What Brown may or may not have done before the shooting does not reflect the underlying problem . . . Those images should not distract from the fact that six gunshots against an unarmed teenager from 20 feet away is excessive force.

Due to this, when discussing Ferguson in the classroom, Newton students must acknowledge that the idea of a “thug image” is rooted in racism. The connection of standard black vernacular or hooded sweatshirts to threats and violence is rooted in a racial prejudice that has already taken too many lives.

Cities with white majorities like Newton can get away with creating these dehumanizing biases and allowing them to impact existing power structures. Here in Newton, white privilege may not have as much to do with police brutality as it does in Ferguson (though I am not one to say it does not), but it has plenty to do with academic achievement and the way that students are viewed by their peers and teachers.

All over the country, prejudice subjects people of color to varying degrees of disadvantage, and regardless of the location, privileged whites have the power to end cycles of oppression. In Ferguson, that means ending police violence and human rights violations.At this school, that means stopping our biases from letting us underestimate and undermine students’ potential, thus making real progress toward closing the achievement gap.