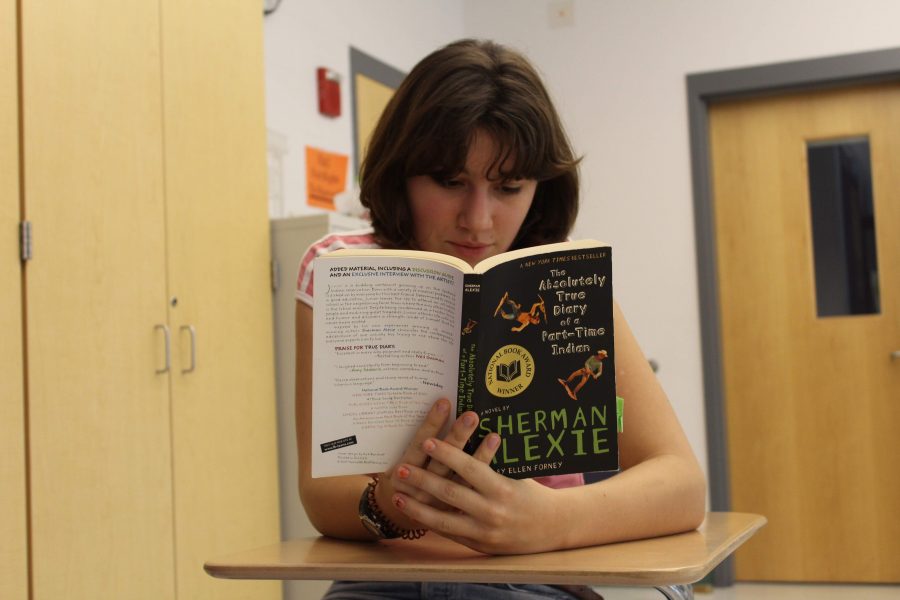

My favorite book that I read in ninth grade English was The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie.

It is the story of a young Native American boy named Junior who lives on a reservation. The book chronicles the trials and tribulations he faces in his community, especially as he transfers into a mostly white school. The book is the only Native American voice represented in the ninth grade curriculum at North (or tenth and eleventh grade, for that matter). While it is not a required book, many teachers feature it in their curriculum for its depiction of a marginalized voice, its colloquial writing style, and Junior’s cartoons, which adorn many of its pages.

In the literary world, many view Sherman Alexie as a Native American luminary—he has won a variety of awards, including the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. Yet last spring, multiple women alleged that he had used his powerful status to engage in sexual misconduct with rising female writers.

These allegations bring up a conundrum regarding art and content produced by people who have used their power to sexually assault or abuse others, and if it is possible to separate art from artist. This year and last year, teachers at North have and will continue to grapple with the choice between teaching a book written by a sexual abuser, or not featuring this marginalized voice.

While some purists may say that it is best to read a book solely as a book, separate from the toil and murk of the world around it, I believe that the context of a book is imperative to understanding its meaning, and importance. The artist creates the art, and as such, I believe that the art is inseparable from the artist. Reading a book without working to recognize its full background—including the author’s background—lessens the reader’s understanding of the book and what meaning they take from it. One way to resolve the struggle of whether or not to teach Absolutely True Diary is for teachers to continue using the book in their curriculum, but to address the issue and open up a conversation.

The example of the issue surrounding this book is a particularly complicated and challenging one. Reflecting on my own experience of reading Absolutely True Diary in ninth grade, I thought about the way teachers treat other books in the curriculum. When I read To Kill a Mockingbird in eighth grade, the class discussed the cultural backdrop of the 1950s and 60s. When I read Romeo and Juliet in ninth grade, we talked about Shakespeare’s life, the Globe theater, and the context of fair Verona. When I read When the Emperor Was Divine in tenth grade, we learned about the Japanese-American internment camps during World War II by reading eviction notices and discussing cartoons from the era.

With the help of this background knowledge, I gained a deeper understanding of each book’s meaning and how history shaped its writing, and vice versa.

In the case of Alexie and Absolutely True Diary, teachers should continue to educate themselves about the book’s background and inform students of the recent events concerning Alexie. This is an opportunity for discussion because when it comes down to it, censorship never does any good—removing this book will do nothing but perpetuate the avoidance of an essential and uncomfortable dialogue about power and patriarchy in this country.

This line of thinking is applicable not only to reading in school, but to the world at large; Absolutely True Diary is absolutely not the only piece of art whose perception has been impacted by the #MeToo movement. Personally, I have grappled with the questions surrounding separating art and artist many times during the past year. Reading A Series of Unfortunate Events as a child, I developed a love of the series’ labyrinthine conspiracies and dry sense of humor. Yet multiple women have accused its author, Daniel Handler, of inappropriate sexual remarks. I’ve been a lifelong fan of Harry Potter, and was delighted to hear that J.K. Rowling was making a series of prequel movies—however, Amber Heard accused one of the movie’s principal actors, Johnny Depp, her former husband, of domestic abuse, and received a restraining order against him. Both these men, as James Dashner, author of the popular young adult series The Maze Runner, Tweeted about himself after accusations of inappropriate behavior towards women, have been “part of the problem.”

These books and movies have impacted me, but learning that the men involved in their making have abused their power to harm women has made me reconsider my emotional connection to them. A year into the #MeToo movement, I am still struggling to figure out how to deal with my conflicting emotions of love and disgust for these works of art.

The only conclusion I have been able to come to is that ignoring an artist’s harmful actions only perpetuates the rape culture surrounding the #MeToo movement. Instead, we need to start a conversation, and use our knowledge about the media to inform our consumption. I don’t need to throw out my copies of Handler’s books or boycott the movie, but I do need to be able to acknowledge both the artistic worth and author’s background in evaluating the work’s meaning.

One concrete way to face this issue has to do with our purchasing power as consumers of media. By buying a book, we are financially supporting its author. To combat this struggle between not wanting to ban the book and not wanting to promote its author, we can support authors who challenge rape culture by buying their books—such as Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson—and in the case of Alexie, to buy books from other Native American voices. This solution is one way to avoid censorship and still be able to acknowledge the artistic worth of the media. It also helps encourage conversation around and pushback against the issues that spawned the movement in the first place.

So no, there is no simple answer to whether or not teachers should continue teaching Absolutely True Diary. And I haven’t figured out if I will see The Crimes of Grindelwald this year, or ever be able to re-read the Baudelaire orphans’ misadventures with the same degree of childish enthusiasm. I don’t fully know how to detach my heart from these pieces of art, and I don’t fully know how to reconcile the tenderness I harbor for them with the disgust I feel towards the men who were involved in their making. But as Alexie writes in the book, “If you care about something enough, it’s going to make you cry. But you have to use it. Use your tears. Use your pain. Use your fear. Get mad.”

Promote dialogue, context to separate art from artist

November 5, 2018

0

Donate to The Newtonite

More to Discover