What may slip under a casual viewer’s perception of a theatrical production is set design, encompassing everything from backdrop to color scheme—the literal nuts and bolts of the show. Yet, according to senior Maggie Quigley, set designer for Theatre Ink’s Clybourne Park, “Design is in general one of the most important parts of theater.”

She added, “It really brings the audience into the world of the show, and it can add another layer to a show.”

Clybourne Park, by Bruce Norris, which will run Nov. 2 through Nov. 4, has two acts, one which takes place in 1959, the other in 2009. The idea for the set may seem simple—according to senior Max Huntington, assistant set designer for the play, the general idea of the set is “a house viewed from the side with one of the walls cut away.” The singularity of this set, though, is apparent in its historical connection.

According to Quigley, the play’s historical link is “so much more direct. We want to be true to life and we want to give the show everything it needs, which is the historical presence.”

She added, “the set acts as a type of character, but it’s the only character that stays the same throughout both acts.”

Yet, the set designers’ challenge for Clybourne Park is that it contradicts this approach—the setting changes drastically between the two acts. Thus, Quigley and Huntington have designed the set so that “you see the same house but see it through a different lens and also 50 years later.”

For example, in the second act, crew members remove the furniture, change the walls, and move cabinets, according to Quigley.

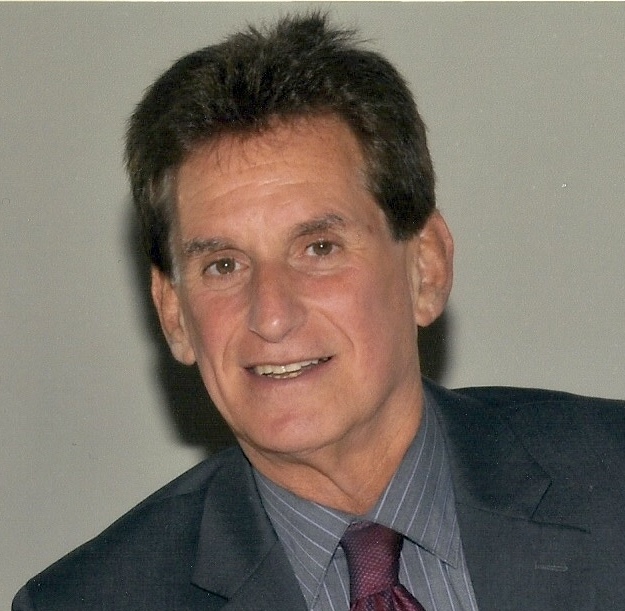

According to Spanish teacher Daniel Fabrizio, director of the play, “the set design of Clybourne Park is an integral part of the production. The audience must be immersed in the world of 1959 in act one, then thrust fifty years in the future in 2009 in act two.”

He added that for this show, Quigley and other set designers “had to design a set that could look like a pristine, well-loved home in 1959, then transforms into a decrepit, vacant home in 2009. The set helps create a mood for the audience and give context to the action in front of it.”

In order to develop a set like this one, the first step is to read the script—and not just once—according to Quigley.

“We read the script. And we read and read and read,” said Quigley. “We read it once for plot, once for what the show needs, and once for concepts.”

After set designers begin to generate a concept for the set, they research. For Clybourne Park specifically, the research was a key part in the process of designing the historically accurate set they hope to build.

“We really wanted to stay true to what it would be like, so we actually researched what this neighborhood would look like in 1959,” said Quigley. “We researched the show and found out that the neighborhood was based on Woodlawn Park, Chicago, and we looked at the type of houses there.”

To get an even more precise idea for how to structure the set, the set designers utilised all the resources they could find online.

“I googled ‘Chicago 1959’, I googled ‘the history of Woodlawn,’ I looked on Zillow, I looked for ground plans and a lot of images and a lot of reading about it,” said Quigley. “I read the Wikipedia page on the changes in Chicago in the last 50 years, and gentrification, and white flight, and all those are concepts that are present in the show.”

Historical accuracy doesn’t end with set design either, but extends to props.

“We have a props team and a props designer,” said Huntington. “If there’s a telephone, they need to find the correct telephone for that era. For example, people are moving out of the house in the first act, so they need to find cardboard boxes that would have existed in the 1950s. You can’t have the Target logo on the side or the Amazon logo.”

After extensive research on architecture and the themes of the show, Quigley and Huntington decided on a type of house to build—a row house—and “looked up ground plans for that house, and then we developed one to fit our show,” said Quigley.

Theatre Ink’s set designers use an online design program called VectorWorks to meticulously design the set and its ground plans.

“For the first bunch of weeks, it’s really just using VectorWorks,” said Huntington. For Clybourne Park, “We had to have the design concept and a rough sketch of what we want done by the time school started.”

The standard building platform for sets is four foot by eight foot, according to Huntington, and designers have to figure out how many of these platforms they need and how many custom pieces they have to make using VectorWorks. They use the program to map out their plans so they can later transfer them from their online state to reality.

To have time to research, design, and build, Huntington said that set designers “start designing months in advance” of the show. Moreover, set designers and the rest of the departments of crew, including the costume department, the lights department, and the sound department, spend hours working on their craft.

“Every single day, I’m working on [the set] for three to five hours, and we’re here all day Saturday,” said Quigley.

Huntington acknowledges the stress caused by his time spent working on the set. “Crew has a pretty heavy influence on the rest of my life. I’m busy every day after school until six o’clock which doesn’t leave much time for homework, and my Saturdays are pretty much taken up.”

During these long hours on the set, “It’s so much problem-solving on a daily basis. I really like problem-solving, and you just get to opportunity to do it nonstop because there’s always problems,” said Quigley.

According to Quigley, a lot of problem-solving comes into play where set design overlaps with the other crew departments and with Fabrizio, who helps the set designers think about how they need to construct their set in regards to the actors. There are many variables set designers have to keep in mind when creating the set, and many have to do with how their themes and research can create a set that is not just pretty, but also functional.

The set designer for a play “will take the vision [the director has] come up with for a script and marry it with their own reading, and the result is a set design that everyone has been able to collaborate on,” said Fabrizio.

He added, “The set designer is able to make the practical look artistic.”

The practicalities of design have a lot to do with the “specifics for the actors,” according to Quigley. “For instance, if an actor is particularly tall, we have to make the walls tall enough at every point,” she said.

She added, “We have a point in the set where the walls are twelve feet but we have a stair platform that is six feet high. We have an actor that’s five foot nine with tall hair and they have to duck on that platform.” This type of information must be communicated with the actors, showing how the departments have to interact.

Furthermore, according to Quigley, “If you have ladders, you have to have a certain type of shoes. You have to make sure the dresses are appropriate. If you have someone on a high area you have to make sure no one can see under their dress.”

Every action one department makes affects the other departments, and that means it is important for set designers to stay in touch with all the other parts of crew.

A lot of this communication happens with crew members “going to production meetings. We have one every week, and that’s where everyone checks in and explains what they’ve been doing that week,” according to Huntington.

He added, “There’s also a fair amount of interdepartmental meeting that goes on outside of production meeting. It can just be like, ‘Hey, lighting people, we changed a thing on the set and we need you to okay it and make sure you can still light things if you change it.’ It’s a lot of designing and meeting with people.”

According to Quigley, “We work on our designs partly side by side and partly in stages, so all of us are present during our design meetings where we talk about what kind of show we want to create.”

The camaraderie of crew and its various departments is another thing that makes set design worthwhile for Huntington and Quigley.

“The people are great,” said Huntington.

Quigley added that what makes set design so fulfilling to her is “the team you’re working with. It’s very rewarding to work with this entire team of 50 people, and everyone is putting their hardest into it every single day.”

Both Huntington and Quigley have learned a lot from their time working on the set with their team.

“I’ve learned how to use carpentry tools, I’ve learned more about wiring and how to wire lights together, and I’ve learned a bunch of theater skills,” said Huntington.

He added, “I’ll never look at a show the same way again. That really changes a lot. You see elements in a show and you start thinking about the crew side of it, like how did they build that, that’s a cool light, that looks really nice, those costumes look cool, all of that stuff. And you stop just thinking, ‘Hey, that’s a play!’”

Another thing Quigley and Huntington have both taken away from their time working on set design and crew is a sense of satisfaction in seeing the finished product of their long hours of work.

According to Quigley, the set “becomes your brainchild after a few months of working on it every single day for at least three hours. It becomes this part of you and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s all of a sudden onstage.’”

Huntington added, “It’s really satisfying to see a finished set with lights on it and actors and costumes and think, I did that. I helped do that. It looks professional, it looks real, and I helped make it,” he said.

While to outsiders, set design may seem like simply designing and building a set, set design is, in the end, according to Quigley, “working as a team to put across such a powerful message.”

And, of course, problem solving.

“When I get downstairs, no doubt there’s going to be six things that have gone wrong just during X-block and we’re just going to have to problem-solve, take one thing at a time, and get through it,” said Quigley. “It’s really rewarding at the end of the day when you’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m exhausted and now I have to go do my homework, but look at all the cool stuff we did today.’”

Behind the scenes of Theatre Ink: Set Design

November 2, 2017

Donate to The Newtonite

More to Discover