by Emily Moss

In November, the Massachusetts Board of Education voted to change the course of standardized testing with a new assessment, unofficially known as “MCAS 2.0,” which will eventually become a requirement at North and at schools across the state. Even before the new Massachusetts test has received an official name, however, it has provoked significant controversy.

The change comes less than a year after Massachusetts piloted another test—created by the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC)—in grades K-8. MCAS 2.0 will draw on both PARCC and the original MCAS, which was first introduced in 1998.

Critics of MCAS 2.0 have raised a number of concerns. Even apart from the substance of the proposed assessment, many dislike the prospect of still more uncertainty and tumult in the state’s testing regime. Literacy specialist Kalpana Guttman, who coordinated PARCC testing at Burr Elementary School last year, noted, “Students were guinea pigs for PARCC, and we’re worried that they will be once again for MCAS 2.0.” She added that implementing the new test so suddenly is “like putting a car on the road without taking it for a test drive.”

Critics disagree about the best alternative, with some calling for a return to the original MCAS and others urging that PARCC be fully implemented.

Supporters of MCAS 2.0, meanwhile, say that the shift will allow state officials to incorporate the strongest elements of the PARCC test, the product of a national consortium, while also giving them the flexibility to tailor assessments as needed to Massachusetts students and permitting them to maintain overall control of the process. In the words of Massachusetts secretary of education James Peyser, quoted in the Boston Globe, MCAS 2.0 will allow the state to draw “on the best of both PARCC and MCAS, while ensuring that Massachusetts is able to control its own destiny.”

The Logistics of MCAS 2.0

MCAS 2.0 will take effect in grades K-8 as early as next year, according to assistant chief of staff at the Massachusetts Department of Education Lauren Greene. At the high school level, MCAS 2.0 will not be a graduation requirement until the Class of 2020, although it is unclear when the class will take the exam.

Superintendent David Fleishman said he expects the new test to be more difficult than the original MCAS, placing greater emphasis on critical and creative thinking.

Fleishman noted, moreover, that the decision to retain state control over standardized testing may also in part have been a response to the intense controversy over PARCC.

“There is growing criticism of testing, and PARCC is symbolic of a national test,” said Fleishman. “What can appear confusing about MCAS 2.0 is that we are told that most of the questions will be similar to PARCC but the state does not want to call the test PARCC.”

PARCC versus MCAS

The state’s decision to switch to MCAS 2.0 appears to have reinvigorated existing debates regarding the costs and benefits of PARCC versus MCAS.

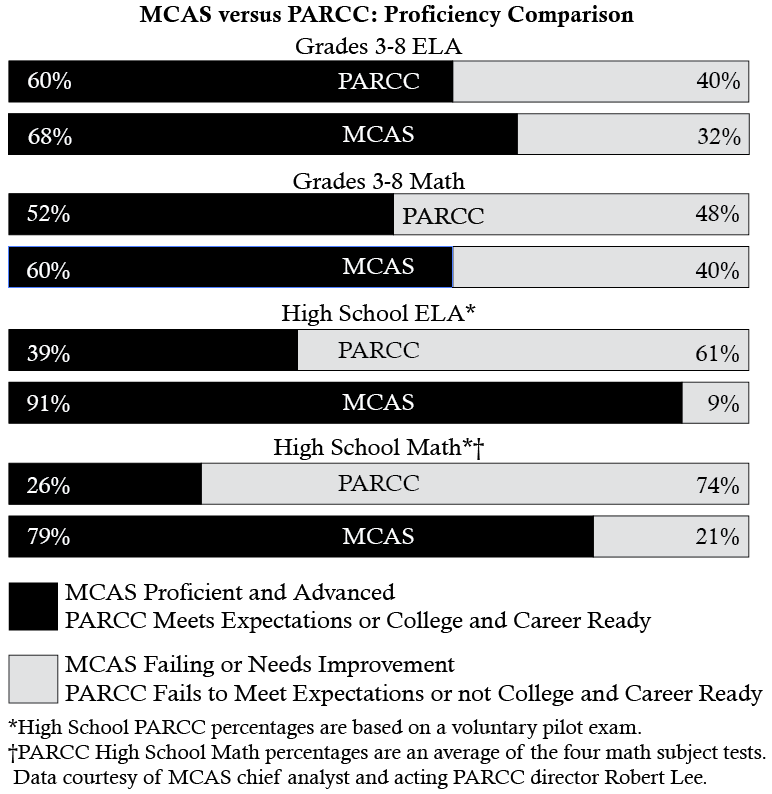

One of the few points that most people involved in the debate agree on is that PARCC is a tougher test. According to the Boston Globe, “results from last year’s pilot demonstrated that students found the PARCC exams significantly more difficult than the MCAS tests.” Beyond that, there is little agreement about the two tests and especially about which test better serves the students of Massachusetts.

Although results from the two tests are not strictly comparable, they are broadly consistent with the Boston Globe’s claim. According to data presented by the MCAS Chief Analyst and Acting PARCC director, approximately 8% fewer Massachusetts students in grades K-8 “met expectations” on PARCC than reached at least “proficient” on MCAS. The same data showed that in voluntary high school pilot tests, only 39% of students were labeled “college and career ready” on the PARCC English Language Arts (ELA) test as compared to 91% who reached at least “proficient” on the MCAS ELA test.

Supporters of PARCC see it as the most advanced assessment of its kind. PARCC chief of assessment Jeff Nellhaus, who previously played a key role in designing MCAS, declared, “MCAS was the best 20th century test. PARCC is the best 21st century test.”

As an example of PARCC’s superiority, Nellhaus argued that PARCC’s emphasis on using evidence to support a claim, particularly on the ELA assessment, aligns more closely with the skills that students need to succeed in college.

“You don’t write an essay off the top of your head in college,” said Nellhaus. In PARCC, “students are asked to read multiple texts and then draw evidence from them to write an extended argument or informational piece.”

However, in part because of its difficulty level, PARCC has sparked strong opposition nationwide. In fact, countless parents across the country have joined an “opt-out” movement in an effort to exempt their children from the test—a move backed by the Massachusetts Teachers’ Association (MTA), which opposes not only PARCC but high-stakes testing in general.

Guttman, meanwhile—after seeing samples of MCAS and PARCC and observing students’ reactions to both tests—said she prefers MCAS, in part because it is more age-appropriate for students. Guttman noted that some of the reading passages on the PARCC test would have been better suited for students one or more grade levels higher.

She added that the wording of the questions on PARCC is often unclear and that she herself sometimes had trouble making sense of the questions on PARCC practice exams.

Guttman is not alone in her concerns. In an open letter to President Obama published in the Huffington Post, one parent wrote, “I have a Ph.D. in English… I got seven out of 36 multiple choice questions wrong on the eleventh grade test. And I had no idea what to do with this essay prompt on the third grade test.”

Other critics of PARCC claim that there was never any reason to overhaul the original MCAS test and the associated standards at all, because Massachusetts already had the nation’s strongest educational system before the introduction of PARCC and the Common Core standards that stand behind it.

A Boston-based policy organization called the Pioneer Institute, which advocates “public policy solutions based on free market principles” and strongly opposes the Common Core, declared in a press release: “the Commonwealth should reject any further participation in the PARCC consortium…. The previous standards and MCAS made Massachusetts the envy of the country and the only state that truly is internationally competitive.”

Although the issue of PARCC versus MCAS often provokes passionate responses on both sides, not everyone believes that either one test or the other has to be judged the winner in a head-to-head contest. Offering a more balanced view, Boston College Professor of Education Michael Russell suggests that neither MCAS nor PARCC is inherently “better” because the two were designed for different purposes: MCAS aims to measure a student’s grasp of state standards from year to year, while PARCC is meant to measure a student’s progress toward college and career readiness.

“Both have their strengths, depending on what you’re trying to do,” said Russell. “It’s like asking, ‘Which is better, a hammer or a screwdriver?’”

The Fight over Feedback

Another area of sharp disagreement about the relative merits of PARCC versus MCAS concerns the quality of feedback given on the two assessments. According to Nellhaus, MCAS 2.0 will likely be similar to PARCC in the style of its feedback and the frequency of its administration.

Nellhaus maintains that at the high school level PARCC provides teachers with better – and more grade-specific – information than MCAS. In those places where PARCC is used in high schools, he says, it is administered in the 9th, 10th, and 11th grades, whereas the math, reading, and writing portions of MCAS are only administered in 10th grade in high schools. This means that instead of relying on a single test that covers high school math in general, PARCC offers tests in algebra I, geometry, and algebra II, allowing teachers to receive “more specific and frequent feedback” on how their students are doing. According to the Massachusetts Department of Education, PARCC also offers annual exams for schools such as North that have an “integrated” curriculum covering elements of both algebra and geometry each year.

Guttman, in contrast, said the score reports students receive from PARCC are disappointing because they lack specificity. This marks a significant departure from MCAS score reports, which detail which topic areas students have mastered and which they still need to improve upon, according to Guttman.

Underlining this concern, Guttman added, “One of the major purposes of testing is to help students and teachers, and MCAS did that for us.” She further observed that “teachers were disappointed about the amount of effort that went into having PARCC happen and the fact that at the end, there was very little information that was useful.”

Computer Screen or Paper?

Beyond the issue of feedback, partisans in the PARCC-MCAS controversy also disagree over the issue of technology: students typically take PARCC tests on computers, whereas MCAS is administered using old-fashioned paper and pencil. Nellhaus insists that the use of computers renders PARCC more relevant to the future of education. “I’m not saying that computers are the be all, end all,” he said, “but that is the environment in which most learning is going to be occurring.”

Guttman, however, observed that many students, especially young students in elementary school, found the on-screen test difficult to navigate. Fleishman reinforced this point, noting that the Newton Public Schools did very well on PARCC as a whole, but that schools whose students took the test using paper and pencil performed better than schools using computers.

As a result, all Newton students taking PARCC will use paper and pencil this year.

The Question of Control

Even apart from the specifics of the tests themselves, proponents of state-level solutions in Massachusetts and around the nation claim that both PARCC and the Common Core undermine state authority and amount to federal overreach. These concerns have become widespread even though both PARCC and the Common Core are products of national consortiums, not the federal government, and states are not technically compelled under federal regulations to adopt either the PARCC tests or the Common Core standards. Nevertheless, the Pioneer Institute declares on its website: “Despite three (3) federal laws that prohibit the federal government from directing, supervising or controlling elementary and secondary school curricula… the U.S. Department of Education (USDOE) has placed the nation on the road to a national curriculum.” A strong opponent of PARCC and the Common Core, the Pioneer Institute has already expressed moderate support for MCAS 2.0 because it will be controlled by Massachusetts officials.

Some experts point out, however, that deviating from the PARCC test through the introduction of MCAS 2.0 could pose certain problems for Massachusetts, which is itself a member of the PARCC consortium. For example, both Nellhaus and Russell suggest that the decision to alter the PARCC test could make it difficult for Massachusetts to accurately compare its educational performance against other states that administer PARCC in unmodified form.

State officials “want to have input on the one hand, but on other hand they want the results to be compared to those of students in other states,” said Nellhaus. “That’s difficult.” One route Massachusetts could take in order to satisfy both of these objectives, in his view, would be to administer the PARCC test as is but to add another section with material developed specifically by Massachusetts officials. That would make the test longer, however, which could raise still other concerns, he said.

Russell added that Massachusetts initially played a significant role in the PARCC consortium but that its status could change now that the state is no longer planning to administer PARCC in its pure form. “It is unclear whether Massachusetts will be able to maintain a strong voice [in the PARCC consortium],” he said.

Concerns about the timeline of MCAS 2.0

Guttman also expressed concern that MCAS 2.0 will be implemented as early as next year in grades K-8. “That they will have the test ready in a year seems hard to believe,” said Guttman.

Fleishman, meanwhile, expressed confidence in Newton’s ability to adapt to the new test, noting that Massachusetts schools experienced another significant transition when MCAS was first implemented in the late 1990s and that “Newton embraced that change.” The district will do the same this time around, he said.

Guttman remains unconvinced. Noting that some of the problems with PARCC probably could have been avoided had its creators spent more time developing the test, she suggested that state officials now should “take a break and design a test worth taking.”

Categories:

State officials to blend MCAS, PARCC in disputed MCAS 2.0

January 25, 2016

0

Donate to The Newtonite

More to Discover